by Grace Cavalieri

Goss183::Casa Menendez © 2008 77pgs.

ISBN: 978-1434896087 Available on www.amazon.com

Lending Her Voice

Grace Cavalieri Projects Herself

Into Her Latest Famous Woman–Anna Nicole Smith

A Review by Geoffrey Himes

(Reprinted with permission from Baltimore City Paper, Dec. 2008)

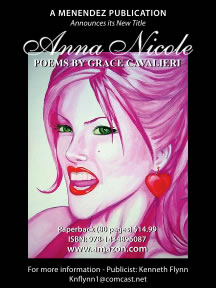

Anna NicoleIn Grace Cavalieri’s latest book of poems, Anna Nicole (CreateSpace), the poems are delivered from the imagined perspective of Anna Nicole Smith, the tabloid celebrity known for her Playboy spreads, her marriage to a millionaire 63 years her senior, and for her own TV reality show. So it’s appropriate that the book’s cover is a deliberately garish painting that gives the pin-up model magenta hair and green eyes.

Anna NicoleIn Grace Cavalieri’s latest book of poems, Anna Nicole (CreateSpace), the poems are delivered from the imagined perspective of Anna Nicole Smith, the tabloid celebrity known for her Playboy spreads, her marriage to a millionaire 63 years her senior, and for her own TV reality show. So it’s appropriate that the book’s cover is a deliberately garish painting that gives the pin-up model magenta hair and green eyes.

“Merrill Leffler, the great poet, had my book lying on his coffee table,” Cavalieri recounts, “and a visiting literary friend of some consequence picked it up and said, ‘What are you reading?’ The friend couldn’t conceive that anything of value could be written about Anna. Merrill tried to defend me, but it’s as if Anna has divided the world into two parts–those who aren’t willing to read about someone they don’t approve of and those who are. Younger people, who think pop culture is all there is to write about, get it. But my girlfriends from Trenton High School in New Jersey, women who buy a lot of books, would never buy this one, because they think Anna’s a train wreck.”

Smith was a train wreck, but that made her more, not less, attractive as a literary subject to Cavalieri, who reads the poems at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda on Sunday. The author of 14 books of poetry and chapbooks and 21 produced plays, Cavalieri is best known as the host of The Poet and the Poem, the radio show sponsored first by Pacifica Radio and then by the Library of Congress and National Public Radio. In recent years, the Annapolis resident has embarked on literary projects where she projects herself into the mind of a famous woman from the past; each project results in a book of poems and a stage play. Her first two subjects were what you might expect: Mary Wollstonecraft, the British feminist who wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792, and Harriet Powers, a 19th-century African-American quilter whose only surviving quilts are now in museums. Cavalieri’s third subject is Anna Nicole Smith.

“I see something alike in all three of them,” Cavalieri claims. “Here’s a British woman who was burned in effigy for saying women should have equal rights, an ex-slave who had to sell a quilt she’d worked half her life on for $5, and Anna Nicole, who was betrayed by her own publicity machine. She only wanted to find out who she was, but they shined her up and pumped her full of pills. She’s a woman who had all the great operatic conflicts, much like the women in Aida and La Bohéme. Her hungers were bigger than life, and so were her failures. It’s great territory for a writer. A lot has been written about her, but the question that no one ever asks is, ‘What did it feel like?’ That’s the question I wanted to answer.”

But how do you put into words the thoughts of someone who gave almost no evidence of thinking? The very thing that made Smith such a compelling subject–her tendency to bypass thought and act on impulse and instinct–made her a challenge for anyone trying to capture her inner monologue. In the 56 poems that make up Anna Nicole, Cavalieri avoids the temptation to turn Smith into the intellectual she never was. Instead, the poet hits on the ingenious strategy of having Smith grope toward a self-awareness that she hungers for but never quite grasps. The poems are not so much about tabloid celebrity as they are about the universal hunt for articulated thought and the elusiveness of that quarry.

“When I’m editing tape for my radio show, I’ll flip back and forth between trash TV and the news, between Nancy Grace and Keith Olbermann,” Cavalieri says. “I remember seeing Anna Nicole after she’d lost her son, when she was on TV in her hospital gown and ponytail and no make-up. Without the make-up, you could see this beautiful face with these great bones and realize, ‘Here is a person who’s a person.’ I saw the vulnerability, and my maternal instincts came out. I wanted to give her a chance to speak for herself. That’s one thing a poet does–give a voice to those who don’t have one.”

The poems include arresting images of Smith’s cleavage being shined for a television appearance and of her breasts being hauled out to feed the sharks of the media. But most of the book is concerned with the unmapped territory of Smith’s mind. In the book’s second poem, “A Tiny Boat Caught Sideways,” Cavalieri describes Smith waking up in her country estate, distracted momentarily by the morning sun and almost forming a thought about nature’s self-sufficiency. You can sense an idea, a connection forming at the edge of Smith’s consciousness, but the evanescent bubble pops and she sinks back into her self-absorption, which is very different than self-awareness. The poem concludes:

. . . the safety of loneliness reached out to her.

She could never see Nature gets

nothing for its efforts, and that

the sun is indifferent to itself. Every day

she woke and spoke to the flat question:

Where is the thrill to being alive?

Even then she lost interest in her own words.

“The challenge in writing about Anna is putting into words a woman who had no words,” Cavalieri says. “But that’s what writing does. It takes the intangible and makes it tangible. You start with nothing and make something. You create characters and tell a story. I didn’t want to use the facts, because everyone already knows the facts. I wanted to reach behind the facts.”

Cavalieri gives her protagonist a dead twin sister, Anima, who murmurs in Smith’s ear, “‘We Can Always Ask For More.’ She keeps hunger in the house that way.” Cavalieri invents a therapist who tries to get Smith to reflect on her issues. He “asked what made each one happy./ Anna said a hit of coke and a shot of tequila,/ then she flushed hot, everyone laughing. She thought she was allowed/ to tell the truth. . . .”

Cavalieri invents a Ph.D. student boyfriend, Rushkin, who encourages his lover to articulate her thoughts. “He tried. OH God how he tried to teach her literary redemption,/ and she talked about redeeming store coupons./ She, to the point of vanity, begged forgiveness. . . .” Cavalieri uses the ravens lurking about Smith’s property as an image for the kind of dark ideas that Smith both craves and fears. “. . .When she opened her eyes the ravens stood/ . . . side by side waiting to peck.”

“She was the epitome of what we do to women,” Cavalieri says of her subject. “We used to burn them at the stake, but now we fill them up with pills and put them on reality shows. They almost feel fulfilled, but the next day they need more pills and more fame to feel almost fulfilled. If you juxtapose men’s images of women they admire and the women’s own voices, they don’t even come close. But Anna didn’t have that voice to juxtapose, so I gave it to her.”

Smith and Cavalieri seem unlikely soul mates. Smith, who died early last year amid a growing blizzard of lawsuits, was a brash, big-boned, big-breasted blonde from Texas. Cavalieri, who married her junior-high boyfriend and raised four now-grown daughters, is a petite brunette from New Jersey. She taught poetry at Antioch College’s Baltimore campus in the early ’70s and was part of the team that founded and operated Washington’s WPFW-FM in the late ’70s. That’s where she started The Poet and the Poem, a weekly, hour-long radio show of interviews and readings heard on public-radio stations across the nation. In the 1980s, she worked for the Public Broadcasting Service and the National Endowment for the Humanities on children’s and arts programming on television. Since then, she has been a part-time teacher and full-time writer.

The poet wears a white sweater over a pale-blue obama for president T-shirt and serves hot lemon tea to her visitor on a backyard deck overlooking a wooded section of Annapolis. When she hands the visitor a copy of Anna Nicole, the book is signed, “Love, from Grace & Anna.” It’s as if the poems–and the play that Cavalieri is now working on–were co-written by the two women, even though they never met.

“I felt as if she were chattering in my ear as I wrote the book, as if we were girlfriends hanging out,” Cavalieri says. “A friend told me, ‘Remember, you’re her sidekick–she has to always be the star, or you defeat the whole purpose.’ That’s true, but there’s a lot of my voice in there, too. You spend a whole year on something, and it inevitably has your voice. I’ve always had dinner on the table for my children, and I’ve always had respectable jobs, so I’m not like her in a lot of ways. But I’ve always had an affinity for women who are held down in one way or another.

“As a writer there’s so much rejection and criticism and people telling you what to do, so I understood Anna in that sense. The difference between us was that I knew that life, like art, is a process of making one thing after another. People will like some of them and not like some of them, but you keep going. Anna never understood that.”

(Reprinted with permission from Baltimore City Paper, Dec. 2008)

Geoffrey Himes is a music critic, and a composer of music and song lyrics. He is the author of hundreds of articles on popular culture as well as a renowned book on Bruce Springsteen.